HOW TO GET MAXIMUM ACCELERATION

Copyright © 1998,

2013 by Mike Clements

1 Introduction

My interest in cars goes back to my earliest memories, and ever since I took my first physics course as a young teenager my friends and I would debate torque, power, gearing and speed. Common debate topics were what determined acceleration vs. top speed, and at what RPM to shift for maximum acceleration. We had a basic understanding of the physics about Force, Mass and Acceleration and their rotational analogs. We also were familiar with the standard phrase, "Torque is acceleration but power is top speed." But somehow this never seemed quite right (it isn't) and these ideas never resolved the debates.

Not until years later did I finally reach a decent understanding of these ideas. I’ll never forget the moment the fog cleared and I mentally “saw” what torque and power really were. I’ve written this down for 3 reasons. First, to solidify my own understanding by going through it step by step. Second, to help others understand it. Third, to get input where my explanation is unclear. There's some math for people who like that sort of thing, but I explain the conclusions in plain English.

2 Basics

Based on the people I've met in car and motorcycle racing, I'd say it is a common belief that torque is the single most important factor determining the acceleration of a car. And in fact, torque really does determine the acceleration of the car. Yet it is torque at the wheel of the car that matters, and this is where the confusion starts. You can get lots of torque at the wheel of the car without having much torque at the engine crankshaft (think motorcycle). And conversely, you can have lots of torque at the crankshaft yet still fail to get much at the wheel (think diesel).

Let's talk about gearing. Anyone who has ridden a 10 speed bicycle intuitively understands it: when you downshift it's easier to pedal but you go slower. It's easier to pedal because the gear ratio is a torque multiplier. You go slower because the cost of that torque multipler is reduction in rotational speed.

Let's quantify this. Suppose gear 1 is spinning at RPM1 with torque T1, and gear 2 is spinning twice as fast with half the torque. If the gear 2 is run through a 2:1 reduction gear the final output spins with torque T1 at speed RPM1. That is, the 2:1 reduction gear halves the speed and doubles the torque. Intuitively, gearing it down sacrifices speed to give it more force.

This demonstrates that torque is not conserved through the drivetrain. One can always trade rotational speed for torque, and vice versa. This is what gearing does. In a car, the fundamental gear ratio is the ratio between the speed of the crankshaft and that of the wheel. If the crankshaft is spinning R times as fast as the wheel, the torque at the wheel is R times that at the crank.

2.1 Examples

Consider a Panoz Roadster powered by a '98 Mustang Cobra drivetrain. The engine produces 300 ft.lbs. of torque. First gear is 3.37:1 and the differential is 3.73:1, so the total gear ratio from the crankshaft to the wheels is 3.37 * 3.73 = 12.57. In 1st gear, the engine crankshaft is spinning 12.57 times as fast as the rear wheels, producing 300 * 12.57 = 3,771 ft.lbs. of torque at the rear wheels.

Consider a '95 Mazda RX-7 (twin turbo Wankel). The engine produces 250 ft.lbs. of torque. First gear is 3.483:1 and the differential is 4.1:1, so the total gear ratio from the crankshaft to the wheels is 3.483 * 4.1 = 14.28. In 1st gear, the engine crankshaft is spinning 14.28 times as fast as the rear wheels, producing 250 * 14.28 = 3,570 ft.lbs. of torque at the rear wheels.

2.2 Pop Quiz

Armed with this knowledge, here's a pop quiz:

Engine A generates 100 ft.-lbs. of torque at 3,000 RPM. Engine B makes the same torque, but at 6,000 RPM. Which engine would you put in your race car?

Many people would take engine A, reasoning that its torque is more "accessible" since it doesn't have to rev as high. However, engine B is far better. It revs twice as high yet makes the same torque. So engine B can use gear ratios that are twice as big without sacrificing speed. Since wheel torque is equal to crankshaft torque multiplied by the gear ratio, engine B can produce twice as much torque at the wheel of the car. That means twice the acceleration.

Many would ask, "why not put those same short gears in engine A?" You can; but it limits your speed because engine A can't rev as high. You'll only be able to go half as fast in any given gear. And every time you shift up to the next gear, you lose acceleration because you're getting less torque at the wheel of the car.

For example, if you both start out in 1st gear you will be racing head-to-head. Suppose with these short gears, car A's redline in 1st gear is 20 mph. As soon as you hit 20 mph, you shift to 2nd gear and your acceleration drops. Yet your competitor in car B stays in 1st gear until 40 mph (since you both have the same gear ratios but he can rev twice as high). So you begin to fall behind and your competitor blows by you. In fact, he's got twice the overall acceleration you have.

Some might argue that engine A would be quicker off the line, even though B would eventually pass it. This is based on the intuitive notion that both cars are initially standing still and engine A has more low end torque than engine B. But in this case intuition leads us astray with two mistaken assumptions.

First, just because an engine achieves its peak torque at high RPM does not necessarily mean it makes less torque at low RPM.

Second, even if the high revving engine does make less torque at low RPM, it only needs half the torque at the engine to get the same torque at the wheel.

Regardless of the gear ratios used with either car, engine B will always accelerate twice as fast on average. Since we assumed that both cars have the same torque and the same weight, we just scrapped the common belief that torque determines acceleration! Making high revs is just as important as making good torque. Engine RPM multiples or leverages the torque at the crankshaft. But RPM alone doesn't make a car go fast, either. RPM and torque are equally important.

3 The Torque Curve

In any gear, the acceleration of a car follows the torque curve. That is, acceleration directly corresponds to engine torque output. Because of this, many people, even experienced racers, believe they should shift gears just past the peak torque RPM before the engine's torque rolls off. This may seem like obvious common sense, but it's wrong.

If you are screaming through 3rd gear with your foot on the floor as the engine is passing through its peak torque RPM, you may think you're getting the best acceleration you can. And you are, for 3rd gear. If you downshift to 2nd, the engine will be spinning at a higher RPM and will be producing less torque. But if you think this means your acceleration would diminish in 2nd gear, then you just fell for a mistake that has fooled thousands before you -- confusing crankshaft torque with wheel torque.

Second gear is a shorter (numerically bigger) ratio so the torque at the wheel of the car is a larger multiple of the torque at the engine crankshaft. In 2nd, the engine may produce more torque at the wheel of the car, even if it has less torque at the crankshaft. It's the product of engine torque and gearing that moves the car, so if you have a little less torque with a lot more gearing, you're going faster.

Here’s another way to look at this: remember that 3rd gear is a taller (numerically smaller) ratio than 2nd, so it provides less acceleration. Suppose the difference between the two ratios is 30% (any percentage will do, but this is typical). That means that when you are accelerating in 2nd gear, the moment you shift to 3rd you will have 30% less torque at the wheel of the car – you will lose 30% of your acceleration. Thus, you should not shift to 3rd gear until you have passed the engine’s torque peak, and the torque has dropped at least 30% from its peak value.

Many racers try to max out their acceleration by “feel”. And since the acceleration of the car follows the torque curve of the engine, you can feel the acceleration decreasing as the engine passes the peak torque RPM. And the moment you feel the car’s acceleration start to diminish, you instinctively grab for the shifter. But then you shift too soon. You’ve maximized the torque at the engine crankshaft, but you haven’t maximized the torque at the wheel of the car. As you rev the engine past the torque peak, you can feel your acceleration gradually diminishing. But if you were to shift, the taller gear ratio would reduce your acceleration even more. So you must resist the urge to shift and let the engine keep revving a bit higher than is intuitively obvious.

3.1 Definition of Power

We said earlier that torque * RPM moves the car. And it happens that Torque * RPM is Power. To be more precise:

P = 2π nt

33000

P engine power in horsepower

π approx. 3.14159265358979323846264338327950288

n engine speed in RPM

t engine torque in ft. lbs.

Removing constant factors (2π / 33000), this equation becomes:

P = nt

Which means power is the product of torque and RPM. Power tells you how much torque you can get at the wheel of the car at any given speed. [1].

We mentioned above that gearing trades rotational speed (in this case, engine RPM) for torque and vice versa. But gearing doesn't change their product: power. Torque is not conserved through the drivetrain, neither is rotational speed. But their product, power, is conserved. This means at every point in the drivetrain, from the engine crankshaft to the wheel, torque * RPM (and thus power) is the same.

3.2 Examples Revisited

The Panoz Roadster had 300 ft.lbs. of torque at the engine crankshaft and 3,771 ft.lbs. at the rear wheels in 1st gear. What is the power? Its Ford Cobra V-8 makes 305 HP at the crankshaft. Since power is conserved, power at the rear wheels is the same as at the crankshaft.

The Mazda RX-7 had 250 ft.lbs. of torque at the engine crankshaft and 3,570 ft.lbs. at the rear wheels in 1st gear. What is the power? It produces 275 HP at the crankshaft. Since power is conserved, power at the rear wheels is the same as at the crankshaft.

The examples demonstrate that torque and RPM are not conserved, but power is. Power is the same at every point in the drivetrain. Gearing swaps rotational speed for torque, and the swap is always linear. Thus their product remains constant, and that product is power. In reality, while power is conserved, it is not actually the same at every point in the drivetrain. Drivetrains lose 10-20% of power due to frictional and inertial losses, so power at the wheels is about 85% of power at the engine crankshaft.

3.3 Some Conclusions

We can draw other conclusions from this mathematical relationship.

First, since power is the product of torque and RPM, power cannot peak until torque is already decreasing. Thus, peak power RPM is always higher than peak torque RPM.

Second, whether the peak torque RPM and the peak power RPM are close together or far apart, depends on how rapidly torque rolls off after it peaks. If torque rolls off quickly after it peaks, the power peak will be close to the torque peak.

Third, every engine has a range of RPM just above the torque peak, where torque is decreasing yet engine RPM is climbing faster than torque is descreasing. Since power is equal to the product of torque and RPM, the engine’s power output is still increasing. Then, at some even higher RPM, torque descreases faster than RPM climbs. The peak power RPM is the transition point where the rate of decreasing torque matches the rate of increasing RPM. Past this point, torque is dropping sharply – “like a rock” as some would say.

Many people like engines that get all their torque down low because "you don't have to rev it up to get to the power". While these engines are easy to drive, they are slower on a racetrack or autocross. Because they get their torque at low RPM, they cannot take advantage of short gearing to multiply that torque. Thus it is no mystery why some of the fastest cars in the world are the hardest to drive. They are designed to achieve their maximum torque at the highest possible RPM. The higher RPM at which they achieve their torque, the more gearing they can use to multiply the torque even higher. If achieving peak torque at 2,000 RPM allows you to use a 4:1 gear ratio, then getting that same torque at 6,000 RPM allows you to use a 12:1 ratio, which means three times the torque at the wheel of the car. That's three times the acceleration, which is the difference between doing 0 to 60 in nine seconds, or in three seconds[2].

Of course, developing strong torque at high RPM doesn’t necessarily mean the engine will have weak torque at low RPM. Some engines manage to develop peak torque at high RPM, but still get 90% of their peak torque throughout the entire RPM range. Features like variable intake geometry and valve timing help engines do this, and they are becoming common.

4 Example Engines

A couple of real world examples should demonstrate how these ideas apply equally well to two completely different engines. First, a 46ci Suzuki Katana motorcycle engine; next, the 454ci Chevrolet V8. In the charts shown below, the green/grey line is torque and the red/black line is power. In these examples, I assume that shifting up one gear lowers the engine RPM by 25% -- if you're at 3,000 RPM in a gear and you shift up, you will be at 2,250 RPM. While this is pretty close for most vehicles, the actual number used does not affect the conclusions (try using a different number and see for yourself).

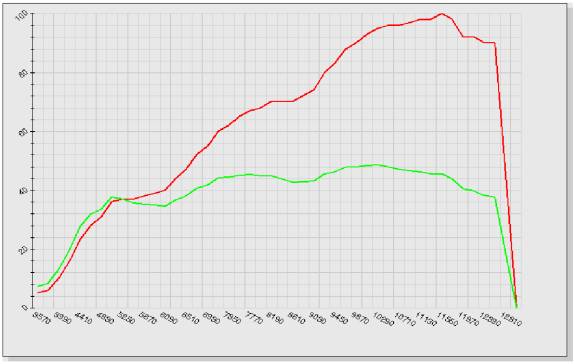

Here is the torque/power curve for the Suzuki:

The torque peak is 48.5 ft.-lbs. at 10,290 RPM; the power peak is 100 hp. at

11,550 RPM. Following the torque curve, you'd shift up just past 10,290 RPM to

keep the engine near its peak torque output. Following the power curve, you'd

shift up just past 11,550 RPM to keep the engine near its peak power output.

Nobody would advocate shifting before the torque peak at 10,290 RPM. The question is how far past this point to go before shifting up to the next gear. In the chart below, each row tells you what happens before and after shifting gears at any point in time. For example, the first row says that if you are at 10,290 RPM in one gear and you upshift, you'll be at 7,718 RPM. The two shaded columns give you the final torque at the wheel of the bike before and after the shift -- in this case, 48.5 before the shift, vs. 34 after the shift. The actual wheel torque will depend on the final drive ratio, but that is irrelevant because it will be proportional to these numbers.

|

BEFORE SHIFT |

AFTER SHIFT |

|||||

|

RPM |

CRANK T |

RATIO |

RPM |

CRANK T |

RATIO |

FINAL T |

|

10290 |

48.5 |

1 |

7718 |

45 |

0.75 |

34 |

|

10500 |

48 |

1 |

7875 |

45 |

0.75 |

34 |

|

11000 |

46.5 |

1 |

8200 |

45 |

0.75 |

34 |

|

11500 |

45 |

1 |

8600 |

42 |

0.75 |

31.5 |

|

12000 |

40 |

1 |

9000 |

43 |

0.75 |

32 |

|

12500 |

38 |

1 |

9400 |

46 |

0.75 |

34.5 |

As the table above shows, the increased torque produced at lower RPM never overcomes the gearing disadvantage of the higher gear. The engine hits redline before reaching the optimal shift point. Thus, the optimal shift point is redline (12,500 RPM).

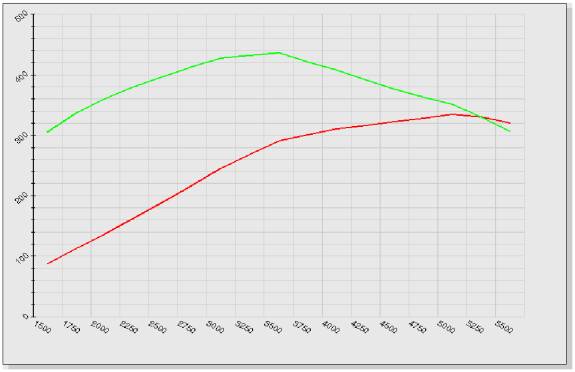

Here is the torque/power curve for the Chevy:

The torque peak is 440 ft.-lbs. at 3,500 RPM; the power peak is 333 hp. at

5,000 RPM.

Again, nobody would advocate shifting before the torque peak at 3,500 RPM. The question is how far past this point to go before shifting up to the next gear. This chart works just like the last one.

|

BEFORE SHIFT |

AFTER SHIFT |

|||||

|

RPM |

CRANK T |

RATIO |

RPM |

CRANK T |

RATIO |

FINAL T |

|

3500 |

440 |

1 |

2625 |

400 |

0.75 |

300 |

|

4000 |

407 |

1 |

3000 |

427 |

0.75 |

320 |

|

4500 |

376 |

1 |

3375 |

435 |

0.75 |

326 |

|

5000 |

351 |

1 |

3750 |

421 |

0.75 |

316 |

|

5500 |

306 |

1 |

4126 |

399 |

0.75 |

299 |

As the table above shows, the increased torque produced at lower RPM never overcomes the gearing disadvantage of the higher gear. As with the motorcycle, the optimal shift point is redline (5,500 RPM). This may comes as a surprise to some big V-8 owners!

5 Another Perspective

This whole discussion becomes much simpler if we take a different perspective. Think about this from the perspective of Energy. Kinetic energy depends on the mass and speed of the car. At rest, a car has zero kinetic energy. Suppose it has kinetic energy E at 60 mph. Energy E represents the amount of work needed to accelerate the car to 60 mph. The faster the engine can perform that work, the faster the car goes 0 to 60. Power is the rate at which the engine performs work.

From this perspective, it becomes obvious that Torque and RPM alone are each irrelevant. If you want to accelerate a certain car to 60 mph, it takes a certain amount of work. If you want to do it in a specific time, say 5 seconds, it takes a certain amount of power. ANY engine that produces that power can do the job. It doesn't matter how much torque the engine generates, or how high it revs. 1 ft.lb. at 1 Million RPM is the same as 1 Million ft.lbs. at 1 RPM. Either way, it's 190 HP.

6 When to Shift Gears

Finally, we're ready to answer the original questions from the first paragraph.

First, what is more important for acceleration, power or torque? The answer should by now be obvious: POWER. The above discussion should make it clear that neither torque nor RPM is alone sufficient to determine acceleration. Since one is force and the other is leverage, it is their product that determines acceleration. And their product is power. The single most important factor determining acceleration is a car's power to weight ratio. For good acceleration you want a light car with lots of power.

Second, what determines the top speed of a car? The answer is much simpler than it seems: once again, POWER. The whole question of acceleration vs. top speed is a red herring. Both depend on the amount of torque at the wheels of the car. And power at the engine crankshaft determines how much torque you can get to the wheels of the car. So the single most important factor determining top speed is the ratio of a car's power to its coefficient of wind resistance. For high top speeds you want an aerodynamic car with lots of power.

Third, when should you shift gears for maximum acceleration? The answer is that you shift on the POWER curve. That means your shift points should surround the peak power RPM. More precisely, the optimum shift point for any engine and transmission is always between the peak power RPM and redline. If you're not inclined to get into the physics of it, just split the difference and shift halfway between the two -- you'll always be very close.

To be precise, the optimum shift RPM is the point at which the engine’s power output is the same before and after the shift. Ride the power curve to the peak and over just far enough so that when you shift, you’re at the same power output but you’re climbing the curve again. Thus, how far past the peak power RPM you go, depends on how close together your gear ratios are spaced. Since most cars have the lower gears spaced farther apart than the higher gears, the optimum shift point is usually redline in 1st gear, dropping by a hundred RPM or so in each successive gear. But since the peak power RPM and redline are usually close together, splitting the difference and using the same point for all gears is a good strategy.

7 Conclusion

Here are the key points which the above discussion and examples have demonstrated:

1. Power is conserved but Torque is not -- do not mistake crankshaft torque with torque at the wheel of the car.

2. Engine RPM and Torque are both equally important for acceleration.

3. Power alone tells you what the engine can do – torque and RPM alone each mean nothing.

4. For maximum acceleration, always shift between the engine’s peak power RPM and redline.

7.1 Common Misperceptions

Armed with this knowledge, let's tackle some common misperceptions.

7.1.1 Towing

You can't tow a load with a high power, low torque engine. To tow a load, you need torque!

There is a thread of truth to this, but only a thread. The people who say it typically don't understand that it is POWER that tows the load. That should be clear already, but if it's not, consider this: Suppose you need to tow a boat up a hill. Any engine can do the job. Any engine at all. Your lawnmower, or the electric motor that rolls your window up and down. The only problem is it's going to take a long time.

Thus the question is not whether the engine can tow the load. Any engine, no matter small, can tow any load up any hill, given enough time. The question is how quickly the engine can tow the load.

How quickly: the time component is absolutely essential and critical. Any work that is ever actually done, is done over a certain amount of time. Power is work over time. It tells you how quickly the engine performs work.

Consider a truck with a 250 HP diesel that makes 500 ft.lbs. of torque. At full throttle, it tows a certain boat up a certain hill at 35 mph. Since POWER is what moves the load, you can pull that same boat up the same hill at the same speed with ANY engine that makes 250 HP. Consider a motorcycle engine that makes 250 HP with only 95 ft.lbs. of torque. Why does it sound ridiculous for this engine to tow the boat up the hill?

It's all about how well the engine can sustain its power output. Since power = torque * RPM, given any 2 of them you can compute the third. We were given power and torque for these engines so we can compute the RPM at which the power is generated. That diesel makes its power at about 2,600 RPM. It's just loafing along while producing full power. The motorcycle makes its power at about 14,000 RPM. How long do you think that motorcycle engine will last spinning at 14,000 RPM, at full throttle, going 35 mph?

The reason high torque diesels are good at towing loads is only indirectly because they have a lot of torque. Torque doesn't pull the load - power does. But since power is torque * RPM, high torque means they operate at low RPM. Making the same power at lower RPM has some benefits:

Because they operate at low RPM, they can produce their maximum rated power continuously even at slow speeds, and are more efficient when producing their max rated power. Most high power, low torque engines cannot produce their maximum rated power continuously at low speeds, and are not efficient when producing their max rated power. They run hotter and require more airflow and cooling.

If it were possible to build a high RPM low torque engine that could operate continuously and efficiently at its maximum rated power output, even at slow speeds, without overheating, that engine would tow the boat up the hill just as well as the high torque diesel. The point is, for towing you don't necessarily need high torque. What you need is an engine that has enough power to tow the load, and can produce that power output continuously and efficiently. High torque engines are a good way to meet those goals and have proven to be practical. Also, diesel engines have higher compression than gasoline engines, which makes diesels more fuel efficient. We'll talk more about compression and efficiency below...

8 Appendix A: Air Density

8.1 Firing Pressure & BMEP

The power an engine can produce depends on air density. If the air sucked into the intake has greater density (and more fuel is added to keep the air-fuel ratio the same), it will produce higher pressure when it ignites, which will push the crankshaft harder, which means the engine develops more torque at the same RPM, which is more power. Alternately, one could say that if the A/F ratio is held constant, more air means more fuel. Thus the engine is burning more fuel with each revolution. If efficiency is constant, burning more fuel in the same amount of time means doing more work, which is more power.

There is a common misperception that an engine’s compression ratio is a measurement of this firing pressure. But the compression ratio is just an abstract geometric number - it does not indicate firing pressure. Compression ratio compares the geometric volume of the cylinder chamber when the piston is at the bottom of the stroke (large), to when it is at the top of the stroke (small). This ratio influences, but it does not determine, the firing pressure. For example, imagine adding a turbocharger or supercharger to an engine. This considerably increases the firing pressure but it does not change the compression ratio at all. In fact, most turbocharged and supercharged cars have lower compression ratio than normally aspirated cars.

Firing pressure is expressed as BMEP which stands for Brake Mean Effective Pressure. The torque an engine produces depends on its BMEP and its total displacement. Essentially, this means torque is the average firing pressure multiplied by the volume in which the pressure is exerted. BMEP is expressed in PSI, but in unitless form it is easy to calculate: BMEP is simply torque divided by displacement.

BMEP = Torque

Displacement

The firing pressure is determined by how full the intake can fill the cylinder during the intake stroke. For example, if the valves are small and don’t open very long, or if the intake manifold restricts the air flow, the engine will not suck in very much mixture and will produce low firing pressures. An engine with a well designed intake manifold, with high flow valves and optimized cam timing, will fill up the cylinder quickly and efficiently, thus producing a high BMEP.

The ultimate goal is to produce an engine that generates a high BMEP and is able to sustain that BMEP even when spinning at high RPM. As RPM increase, this is hard to do because there is less time to fill up the cylinder. That is why high revving engines use 4 or more valves per cylinder, variable intake runners, and other technologies to get the engine to “breathe” at high RPM.

Most normally aspirated gasoline engines produce roughly the same BMEP, which means an engine’s peak torque is more or less linearly related to displacement. If you compute the BMEP for just about any gasoline engine from Hondas to Ferraris to Fords to motorcycles, you'll find them suprisingly close.

For example, consider the Katana 750 engine versus the 454ci Chevy above. The Katana 750 has 48.5 / 46 ci = 1.05 ft.lbs. per cubic inch. The Chevy 454 has 440 / 454 = 0.97 ft.lbs. per cubic inch. It's hard to image two more different engines, and one is 25 years older than the other, yet their BMEP is almost the same (only 8% different).

Engines that rev higher usually have higher geometric compression ratios even though their BMEP is the same as lower revving engines. The higher geometric compression ratio is used to help increase the firing pressure which would otherwise drop because there is less time to fill the combustion chamber at high RPM. Conversely, increasing the geometric compression ratio of an engine without making any other changes, will increase the BMEP.

8.2 Measuring Power

If on a hot afternoon the air is less dense than the cold morning air, then the engine’s BMEP will drop. A drop in BMEP means less torque at the same RPM, which is less power. Since the ambient air density typically varies 5% to 10% above or below “normal”, this has a significant effect on the power an engine produces. Thus, when measuring the power output of an engine it is important to correct the measurement to “standard” air density. This correction may be upward or downward, depending on what we define as “standard” and what were the conditions during the test.

What we are talking about is known as RAD, which stands for Relative Air Density. RAD is expressed as a percentage, which at ground level under normal conditions is usually somewhere between 90% and 110%. Since air density is determined by temperature, pressure and humidity, there are many different conditions that all equal 100% RAD. For example:

60 degrees F, 30” Hg, 0% humidity = 100% RAD

62 degrees F, 30.3” Hg, 40% humidity = 100% RAD

70 degrees F, 30.5” Hg, 0% humidity = 100% RAD

Thus, the optimum conditions for maximum power are low temperature, low humidity and high pressure.

There are two standards commonly used for correcting power: STD and SAE.

STD is defined as: 59 F, 29.92” Hg, 0% humidity. It is the same thing as 100% RAD.

SAE is defined as: 77 F, 29.23” Hg, 0% humidity. It is the same thing as 94.4% RAD.

Suppose you dyno test your engine and measure 100 HP. You determine that the atmospheric conditions during the test were equivalent to 105% RAD. That means the air was 5% denser than “normal”, thus your engine would produce 5% less power under “normal” circumstances. Your STD corrected power is 95 HP, and your SAE corrected power is 90 HP.

The STD or SAE correction is not correcting for drivetrain losses or friction. It is merely correcting atmospheric conditions. For example, one could have an SAE corrected rear wheel horsepower, or an SAE corrected brake horsepower.

8.3 Forced Induction

Forced induction refers to using a compressor on the intake of an engine. The compressor dramatically increases the density of the incoming air, producing significantly higher BMEP, torque and power. Superchargers and turbochargers are the two primary methods of forced induction. The difference between them is what powers the compressor.

A supercharger is powered directly from the crankshaft of the engine. Normally, it is powered by installing an extra pulley in the serpentine belt. Some of the power the engine produces, goes into to the supercharger instead of going to the wheels of the car. But the supercharger adds more power than it draws. That is, the additional power gained by increasing the BMEP, is greater than the power required to drive the compressor.

A turbocharger is powered by inserting a fan in the exhaust. As the exhaust gases flow past the blades of the fan, they cause the fan to spin. The fan is connected to another fan on the intake, which is the compressor. Thus, the intake compressor is powered by the moving exhaust gases. As the engine revs higher, the exhaust gases have increased energy and velocity, which provides greater power to the compressor, which increases the intake compression, which increases BMEP. The turbo fans do impede the exhaust gases, but the impediment they introduce is much smaller than the drag a supercharger draws from the engine crankshaft. Without the turbo, the energy of the exhaust gases would have been unused, so the turbo is powered by harnessing otherwise unused energy. Because of this, turbochargers are usually more efficient than a supercharger. Compared to a supercharger, the same level of boost from a turbo provides greater additional power because less of the power it generates is lost driving the compressor.

The drawback to turbos is design complexity. It is harder to engineer a turbo because one must place an extremely light, low friction, efficient fan directly into the incredibly hot exhaust of the engine. It is difficult to overcome the engineering difficulties. Superchargers are less efficient, but easier to design and build.

One interesting advantage of forced induction is that it can make the engine totally impervious to changes in atmospheric conditions. If the relative air density is low, a computer controlled boost monitor can dial up more boost, essentially driving the compressor harder so the density of the intake charge is the same. This is especially effective on airplanes. As the plane gains altitude, the engine computer dials in more boost to compensate. The use of superchargers was pioneered during WWII on aircraft engines such as the Rolls Royce Merlin.

9 Appendix B: The Torque Curve

All of the examples so far ignored the shape of the torque curve. This is essential to simplify the problem and highlight the physical effects at work. But now it is time to drop this assumption for a closer look at reality.

While it is true that power determines acceleration, and that the optimum shift point is always between the peak power RPM and redline, there is more to the story. Since F = ma, and F is determined by power, one might expect to calculate the acceleration of any car given only its power to weight ratio. For example, a stock 3rd gen RX-7 can accelerate at 1.09 G (3099 lbs. thrust / 2850 lbs. weight) in 1st gear. From this one might assume that it can go 0 - 60 in 2.5 seconds – which is half its actual 0 - 60 time of about 4.9 seconds. Why is it off by a factor of 2? Our estimate would have been accurate only if the car did 0-60 entirely in 1st gear, and if the engine had a perfectly flat torque curve. But the car spends some of its 0-60 run in 2nd gear, where it has less acceleration. In addition, even in 1st gear it accelerates that fast only as it passes through its peak torque RPM. Throughout the rest of the RPM range, it is producing less torque and thus accelerating slower.

The power to weight ratio provides a good "first guess" rough approximation of acceleration. Indeed, one rule of thumb is to divide the curb weight by the horsepower, then take half this number as the 0-60 time in seconds. But actual results can vary from this calculation. The problem is that no engine has a perfectly flat torque curve, so it's only producing its peak torque and power throughout a fraction of its RPM range. This fraction can be relatively small or large, depending on the engine. Big V8s tend to have relatively flat torque curves, while small, high revving engines tend to have increasing torque with RPM. But these are only general tendencies and there are plenty of exceptions. Indeed, the reason I chose the Suzuki GSX 750cc engine in the previous example is that it is one of very few high power, high RPM engines that has a relatively flat torque curve.

An engine of any size can be designed with a flat torque curve, or it can be designed to develop greater high RPM peak power by sacrificing power at lower RPM, or it can be designed in the opposite manner -- to develop strong low end and midrange torque at the expense of high RPM power. Each design optimizes the engine for different purposes. Which is best depends on how the engine will be used.

For all-out maximum drag racing acceleration, one needs the best possible power to weight ratio. We might like a monster V8 or larger engine with tremendous power output, but it's big and heavy, which impairs the power to weight ratio. If we can get that same power from a smaller, lighter engine, then the reduced weight will give us even greater acceleration (in addition to a better balanced car, better cornering and better stopping). We can do this if we are willing to engineer it carefully and make some sacrifices. In the comparison of the two engines above, observe that the Chevy is about 10 times larger than the Suzuki, but has only about 3 times more power, and the Suzuki’s torque curve is almost as flat as the Chevy’s. Of course, this is partially the effect of 25 years of engine design improvement (1969 to 1994).

To get a certain amount of power, we need a combination of torque and RPM. It is harder for a smaller engine to generate the same amount of torque, but it is easier for it to rev higher. So if we can design a smaller, lighter engine that revs higher, we can get the same amount of power as a larger, heavier engine. The trick is to get our torque at high RPM. This is not easy, because in a piston engine we are fighting the inertial losses of a piston moving back and forth, which grow exponentially as RPM increases linearly. To minimize the inertial losses of the pistons, we can use a shorter stroke and larger bore to get the same overall displacement. The shorter stroke means that at any given RPM the piston is moving slower, which reduces the inertial losses at high RPM. But shortening the stroke gives the downward force of the piston less leverage on the crankshaft, which gives the engine less torque. However, with more RPM and less torque we are likely to have the same power, and we've obtained it from a lighter, smaller engine. The larger bore gives us room to use larger valves, which lets the engine “breathe” better and get more mixture into each compression stroke. In addition, we can use overhead cams instead of pushrods to reduce inertia in the valve train, and we can tune the valve timing and the exhaust to resonate at high RPM. All of these together will enable the engine to continue developing torque at high RPM, which gives us more power. But they also can reduce the low end torque, which means the engine lugs at low RPM. This narrows the operating RPM range. Engines like this are often called "peaky", "pipey" or “binary” since they are fairly weak at low RPM, and come on strong at high RPM.

To compensate for this, we would want to use gear ratios spaced close together so that when you shift to the next higher gear, the engine RPM drops only a little bit, staying in the high RPM range where the engine has good power. You end up with a car that is harder to drive, because the driver has to pay close attention to his gear and speed to keep his RPM up. But it will accelerate faster because smaller, high revving engines have inherently greater power to weight ratios.

One way to view this is that RPM and torque are equally important for producing power, and RPM is lighter than torque.

However, drag racing is not the only form of racing, perhaps not even the most exciting. If the race involves turning, the driver will have to slow down and speed up while turning and braking. Slowing down without downshifting could make our pipey engine fall off the power curve. But we'd like to avoid constantly having to shift gears. In this case, peak power becomes less meaningful, especially if it is achieved only in a narrow RPM range. The shape of the torque curve becomes more important.

An engine with a flat torque curve is consistent and predictable. Put your foot down and it accelerates through each gear at a constant rate. Contrast this with an engine like the turbocharged Wankel in the 3rd generation RX-7, which doesn't do much until it hits 4500 RPM, at which point the high speed turbo kicks in full boost at the same time the Wankel's natural torque curve is increasing. Such an engine produces more peak power, but is less consistent and less predictable because it sacrifices low RPM power. When you put your foot down, the engine responds in a significantly different way, depending on the gear and RPM.

When driving through curves, it is easier to control the car if the engine has a flat torque curve. With a flat torque curve, you can brake for the turn and when you hit the gas again you'll always have the same acceleration. You can't fall off a flat torque curve!

10 Appendix C: Gearing Revisited

Most drag racers spend a lot of time thinking about the amount of time the engine spends in the power band; i.e. the distance between the shift points. If your gears are spaced too far apart, then your engine drops out of power band after each shift, and has to climb back up the power curve. People want to get the gears spaced closer together so the engine stays in the power band. But there is a downside: if the engine is already staying in the power band with the current gears, then putting the ratios closer together slows you down because you’re not getting any extra power, but you are shifting gears more often and losing time. There is a happy optimum gear ratio spacing for every engine, based on the shape of the engine's torque curve.

Many drag racers use ridiculously short (high ratio) differential ratios in their cars, some nearly twice the stock gearing. Many of them think this moves their shift points closer together, or enables the engine to spend “more time in the power band”. It also makes the car feel faster, since it is pulling harder in every gear (though at lower speeds).

But this issue is a giant red herring.

You might wonder why we never considered the differential ratio in any of the examples so far. Changing the differential ratio has no effect on the spacing of the gear ratios. For example, if with a stock 3.27 differential ratio, a shift from 2nd gear at 6500 RPM starts 3rd gear at 4750 RPM, this also will be true with 4.1, 4.3 or any other differential gear ratio you choose. If the percentage difference in the gear ratio between two gears, say, 2nd and 3rd, is X %, then the percentage drop in RPM when shifting from one gear to the next is also X % -- no matter what your differential ratio is. Using a shorter gear ratio in the differential does not move the shift points closer together. So if you think the gears are spaced too far apart, you better replace your transmission. It's the tranny gearing that keeps the engine in the power curve, not differential gearing.

You might be wondering what the differential ratio does do. It affects two key areas: getting off the line and shift points. The first is the most important. You want a differential ratio that is big enough (short enough) to make your 1st gear acceleration traction limited. To be more precise, you want to use the lowest (tallest) differential ratio, that is still high (short) enough to make your 1st gear acceleration limited only by tire traction.

Why is this optimal? If you gear taller than this, you will not be getting all the acceleration you can and you'll take longer to climb the power curve. If you gear shorter than this, you will not get off the line any quicker (because you were already traction limited), but you will hit your shift points sooner and spend more time shifting gears.

The second (less important) factor in choosing a differential ratio is shift points. You want to be near -- but not at -- redline when you drive through the finish line. For most cars, this usually means you want 3 tall gears, or 4 short gears. If you're bumping the rev limiter just before the end of the run, it's better to use a slightly taller gear to finish in that gear without hitting the limiter, thus avoiding time lost in the extra gear shift. On the other hand, if you're well below redline when you pass the finish line, you could use a shorter ratio and get more acceleration, without requiring an extra shift.

But the first factor – launching – is usually dominant. So even if you are well below redline at the finish line, using a shorter gear ratio will make you faster only if you have the traction to handle it. If not, it will slow you down.

Also remember that you can fine tune your differential gearing by your selection of rear tire sizes. Of course this applies only if you have a rear wheel drive car. But we already knew you had rear wheel drive, else you'd be a ricer and you would not be reading this.

In summary, the primary points regarding differential gearing are the following:

1. Differential gear ratios have no effect on the optimal gear shift RPM or on the amount of time the engine spends in the power band.

2. If you are already traction limited in 1st gear, then bigger differential ratios will slow you down.

3. Bigger differential ratios will make you faster only if both of the following are true: You have enough traction to handle it, and the improvement is enough to compensate for any extra shifts required by the shorter gear ratio.

11 Appendix D: Atkinson Cycle

Most 4 stroke piston engines run in what is known as

Otto Cycle:

Some modern engines claim to operate in Atkinson Cycle but this is a misnomer. Atkinson cycle was invented in the 1800s as an engine with an articulated piston rod giving a short intake stroke with a long power stroke to maximize efficiency. The system that modern engines use, calling it by the same name, is quite different yet serves the same goal with a simpler design. That goal is to increase efficiency.

As explained in this article, for maximum power,

a 4-cycle engine crams the cylinder as full as possible during the intake stroke.

In Atkinson cycle, the cylinder is only partially filled during the intake stroke.

This improves efficiency in two key ways:

Put conversely, there are 2 drawbacks to cramming the cylinder as full as possible:

As you might guess, the increased efficiency that Atkinson cycle provides comes at a price: lower power output. This makes it non-useful to racing, but it's a clever idea, and an engine can be designed to operate in either Otto or Atkinson as needed.

In Otto Cycle the intake valve closes at the bottom of the intake stroke. In Atkinson Cycle, the intake valve remains open longer - it closes late, after the cylinder has risen part way up the compression stroke. Some of the mixture drawn in during the intake stroke is pushed back out the intake valve before it closes. Why would anyone do this? It seems counterproductive! It means less mixture captured in the cylinder, which lowers BMEP, torque and power. But this smaller amount of mixture is easier to compress, so there is less pumping resistance. And when ignited, it can fully expand during the power stroke. Ideally, at the end of the power stroke the mixture is fully expanded and the pressure in the cylinder equals atmospheric. This means no energy is wasted.

Because modern engines implement Atkinson cycle with valve timing, they can shift between Otto and Atkinson cycle automatically on demand. At low RPM, part throttle, you aren't demanding lots of power. The engine shifts intake valve timing to run in Atkinson Cycle for maximum efficiency. As the throttle is opened, or as the engine revs higher, you are demanding power. The engine shifts intake valve timing to Otto Cycle for maximum power.

12 Appendix E: Mathematical Derivation

Earlier, we presented the equation showing the mathematical relationship between power and torque. Here is where that equation comes from.

Torque is the rotational version of Force, expressed in units of Newton Meters or Pound Feet. Revolutions are the rotational version of distance, usually expressed in Radians. Work is the transfer of energy from one object or system to another, expressed as the product of force and distance. The rotational version of work is expressed as the product of torque and radians. Power is the rate at which work is performed, expressed in any system as work divided by time, otherwise known as work per second.

In the metric system, 1 Joule is the same as 1 Newton Meter. Thus, with Power expressed in Watts, we would have:

P = Newton * Meter * radians

second

But since radians are unitless, we have

P = Newton * Meter

second

But the equation presented in section 3 of this document was expressed in British units. So we must convert the units.

1 Horsepower = 746 Watts

1 Joule = 0.738 Ft. Lbs.

1 rad = 1 / 2π revolutions

1 second = 1 / 60 minute

1 foot = 0.305 meter

Now remember the original equation:

P = 2π nt

33000

Thus, the 33,000 is an approximation that from the expression (746 * 0.738 * 60), which is actually about 33033. And the 2π factor comes from converting radians to revolutions.